Ocean acidification may reduce sea scallop fisheries

by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution 23 Sep 2018 13:19 UTC

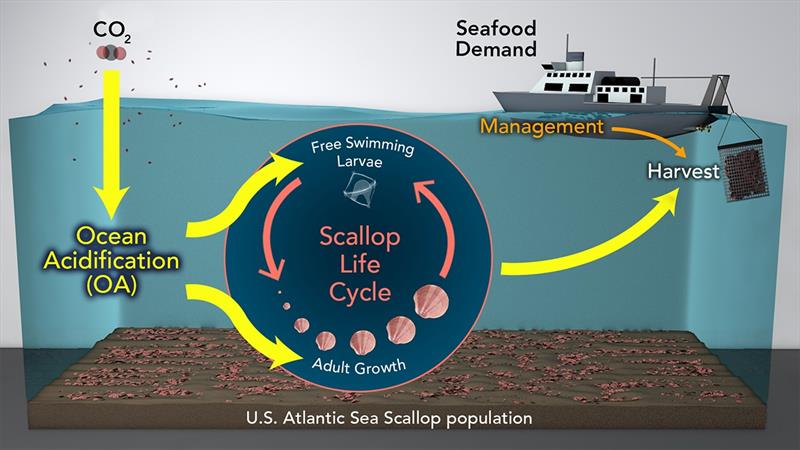

Conceptual diagram of the model that links sea scallop population dynamics, (pink) possible climate change and ocean acidification impacts (yellow), and economic development and management strategies © Natalie Renier, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Each year, fishermen harvest more than $500 million worth of Atlantic sea scallops from the waters off the east coast of the United States. A new model created by scientists at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), however, predicts that those fisheries may potentially be in danger. As levels of carbon dioxide increase in the Earth's atmosphere, the upper oceans become increasingly acidic—a condition that could reduce the sea scallop population by more than 50% in the next 30 to 80 years, under a worst-case scenario. Strong fisheries management and efforts to reduce CO2 emissions, however, might slow or even stop that trend.

The model, published in the journal PLoS One, combines existing data and models of four major factors: future climate change scenarios, ocean acidification impacts, fisheries management policies, and fuel costs for fishermen.

"What's novel about our work is that it brings together models of changing ocean environments as well as human responses" says Jennie Rheuban, the lead author of the study. "It combines socioeconomic decision making, ocean chemistry, atmospheric carbon dioxide, economic development and fisheries management. We tried to create a holistic view of how environmental changes might play out across different aspects of the sea scallop fishery," she notes.

Since the oceans can absorb more than a quarter of all excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, fossil fuel carbon emissions can cause a dip in ocean pH as well. That acidity can corrode the calcium carbonate shells that are made by shellfish like clams, oysters, and scallops, and even prevent their larvae from forming shells in the first place.

According to Rheuban, no existing studies have been published that can show the specific effects of ocean acidification on the Atlantic sea scallop. To estimate its impact in the model, she and her colleagues incorporated a range of effects based on studies of related shellfish species. Combined with estimates of changing water chemistry, this new model lets scientists explore how plausible impacts of ocean acidification may change the future of the scallop population.

Rheuban and colleagues tested four different levels of impact in each of the four different factors influencing the model, ultimately creating 256 different scenario combinations.One group of scenarios looks at possible pathways of how ocean acidification may impact scallop biology. Another examines different levels of atmospheric CO2, including one future where emissions continue to skyrocket, and one where they fall due to aggressive climate change policy. A third set includes a range of future fuel costs, which themselves are related to climate change policies. Higher fuel costs, Rheuban notes, can lead to fewer active fishing days, reducing stress on the fishery itself, but also reducing profitability and revenues of the industry. The fourth and final set involves different federal fisheries management techniques.

Fishing policies for some shellfish, like oyster, clams, and bay scallops, are regulated by state or local governments, each of which follows its own set of rules. Sea scallop fisheries, however, are located well offshore in a region stretching from Virginia to Maine, so are regulated mostly by the federal government. With only one set of rules covering most sea scallop fisherman, it's possible to fit them into the model.

"The current sea scallop fishery is so healthy and valuable today in part because it is very well managed," says Scott Doney, a co-author from WHOI and the University of Virginia. "We also used the model to ask whether management approaches could offset the negative impacts of ocean acidification."

In all of the model's possible scenarios, high levels of CO2 in the atmosphere consistently led to increased ocean acidification and fewer sea scallops, despite introducing stricter management rules or even closing part of the fishery entirely.

"The model highlights the potential risks to sea scallops and likely other commercial shellfish fisheries of unabated carbon emissions to the atmosphere" adds Doney.

Over the next 100 years, under the worst-case ocean acidification impacts, the model's 'business-as-usual' scenario shows a sea scallop decline of more than 50%, while a scenario with proactive climate policy shows only a 13% reduction.

"The model shows that reductions in fossil fuel emissions due to climate policy might have a big impact on the sea scallop fishery," concludes Rheuban.

Also collaborating on the study were Scott C. Doney of WHOI and the University of Virginia, Sarah R. Cooley of the Ocean Conservancy, and Deborah R. Hart of the NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center. The research was supported by NOAA Grant # NA12NOS4780145 and the WestWind Foundation.

This article has been provided by the courtesy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.